Africa must unite to tackle food, climate, and biodiversity challenges through agrifood systems transformation

As part of the Extraordinary African Union Summit on the Post-Malabo Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme held in Kampala last week, the Zero Hunger Coalition organised, together with its partners (BMZ, CGIAR, GIZ, GAIN, the governments of Benin, DRC, Cameroon, Madagascar, Somalia and Zambia, the Shamba Centre for Food & Climate, the UN Food Systems Coordination Hub, and the World Food Programme), an official side event to explore the convergence between the food, climate, nutrition and biodiversity agendas.

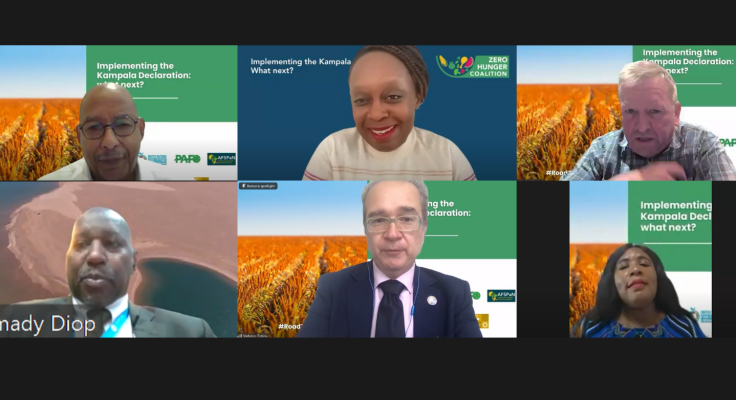

Moderated by Dr. Namukolo Covic of CGIAR, this high-level event brought together representatives from agricultural ministries in Cameroon and Madagascar as well as international experts from GAIN, PAFO, World Food Programme, the Zero Hunger Coalition and BMZ.

The event kicked off with a keynote address by Dr Ibrahim Mayaki, Chair of the Zero Hunger Coalition, who emphasised the critical role of cohesion, partnerships, and acceleration in driving Africa’s agricultural transformation. A common way of planning and implementing food systems is needed. Doing so requires partnerships at the national level – between ministries – as well as the international level between partners in order to mobilise more finance, share experiences and anticipate constraints.

“The Zero Hunger Coalition exists to facilitate this acceleration,” he remarked, stressing the rapid population growth and climate changes underway in Africa which demand proactive strategies to ensure food security.

Expanding the food systems perspective

Representatives of the ministries of agriculture in Cameroon and Madagascar discussed the challenges that the countries face and how they are being addressed.

A study by the Coalition has highlighted that transforming Madagascar’s agrifood systems, eradicating hunger, and doubling the income of small-scale farmers while restoring the environment will require significant investment, estimated to be 24% of the country’s GDP. This reflects the severe challenges Madagascar faces, with nearly half of its population experiencing food insecurity. In response, Madagascar is taking decisive action. As part of its agrifood systems transformation, the country is adopting an inclusive, multi-sectoral approach focused on supporting farmers, strengthening agrifood businesses, and building resilience across the sector.

In Cameroon, the Ministry of Agriculture has reinforced the need for a multisectoral approach. “We are expanding our food systems lens beyond agriculture to also include health and infrastructure,” noted Tobie Ondoa Manga, speaking on behalf of HE Gabriel Mbairobe. Cameroon has privileged collaboration with international coalitions, including the Zero Hunger Coalition, in order to learn from other countries and share experiences.

Bringing in international partners

Paul Garaycochea from BMZ noted the historic importance of the Kampala Declaration which must now be translated into action. He called for greater ambition from international partners, noting that “convergence must begin at the international level, with global policies and frameworks adopting a food systems approach.” However, this is currently not the case with global agendas on climate, biodiversity and food systems considered in separate silos.

Stanlake Samkange from the World Food Programme called for a shift in focus from emergency interventions to resilience-building in the long-term. He also highlighted the economic potential of buying locally, pointing to the organization’s $6 million annual food procurement budget in Africa which could be supplied by local markets. However, doing so will require transforming food systems. Such a transformation should be led by countries with engagement from a broad range of stakeholders, including climate and energy experts.

Dr. Lawrence Haddad made a compelling case for prioritising nutrition. “If we care about economic growth, the viability of our health systems and climate resilience, then we must invest in nutrition. Nutrition is essential for development.” This can be achieved through school meal programmes and social protection services, which, if sourced locally, can stimulate local production.

Will the Kampala Declaration succeed?

Ibrahima Coulibaly from PAFO asked a critical question: “No progress has been made for farmers, why will the Kampala Declaration be any different?” For Mr Coulibaly, two key challenges must be addressed before any meaningful progress can occur.

First, African institutions are weak and dysfunctional. Despite agriculture being on the agenda for the last 20 years, there is a lack of political coherence at the national level. Second, while dialogue is currently underway among government technocrats, it often fails to bring in and listen to farmers, i.e. the very individuals who are directly impacted. For these reasons, Mr Coulibaly called for greater political coherence and stronger government support to help farmers and stabilise their incomes.

But can the objectives of the Kampala Declaration be achieved? Dr Haddad expressed cautious optimism, providing three reasons for hope. First, the stakes are much higher now than in previous CAADP phases (Maputo in 2003 and Malabo in 2014) making the need for success more urgent. Second, the commitment from governments is much higher. And, finally, the rise of digital tools such as social media has increased transparency, making it harder for governments to conceal unflattering information or inaction.

Dr Haddad also offered a key caveat; “Transformation requires change from all of us. Everyone – from farmers to presidents – must make changes and this will likely mean taking action that may be uncomfortable,” he concluded.